Transfer tales

Share

OAG’s chief analyst, John Grant, explains why the battle for connecting passengers is likely to heat up in the Middle East.

Believe the many stories written about airports, and the world is dominated by the super connectors in the Middle East. Indeed, the major airports and airlines are outstanding examples of how an airport can transform an economy and raise the profile of any country.

And yet, in the recently released OAG Megahubs report, which ranks the world’s most connected airports, there is plenty of room for the major Middle East hubs to climb the ranks, with Dubai ‘leading’ in fifteenth spot, Riyadh twenty-sixth and Doha in thirty-fourth place.

Ten years of Megahubs results highlight how difficult it is to break into the top ten, but also the challenge of keeping the same spot every year.

No one doubts the quality offered by the three Middle East hubs of Dubai, Riyadh and Doha, but will they be able to achieve top Megahub status?

And what does the future hold for the broader Middle East market with the two new super hubs developing in Saudi Arabia,and Dubai World Central taking shape in the middle of the next decade?

While demand continues to grow, a key question surrounds how each airport will evolve in the next decade and how they will be impacted in a part of the world where aviation and politics frequently go hand in hand.

One thing is clear: change is coming. But where, when and how are worth looking at in more detail.

THE IMPACT OF SAUDI ARABIA’S VISION 2030

While the Vision 2030 project may have been a tad ambitious in terms of passenger numbers, traffic will probably double over the decade as the established Saudia network expands and the new Riyadh Air launches services.

Recent aircraft orders for both airlines reflect the commitment to growth in the Kingdom, which has the distinct advantage of a large domestic market; a feature that no other major Middle East market can offer.

While Saudia continues to slowly build its network, supply chain issues mean the pace of development at Riyadh Air has been much slower than originally planned.

London Heathrow should start this winter alongside other more regional services, but the airline is some way behind in its plans.

The ultimate network will pivot around their new airport facility and for every London or Paris there will be a Bangkok or Manila.

For Riyadh Air the crucial development of connecting traffic will involve direct competition with established regional carriers which have high service levels and frequency across the globe.

It is, of course, impossible for Riyadh Air to replicate the networks of Emirates and Qatar Airways overnight, so selective market development will be crucial in the early years of operation.

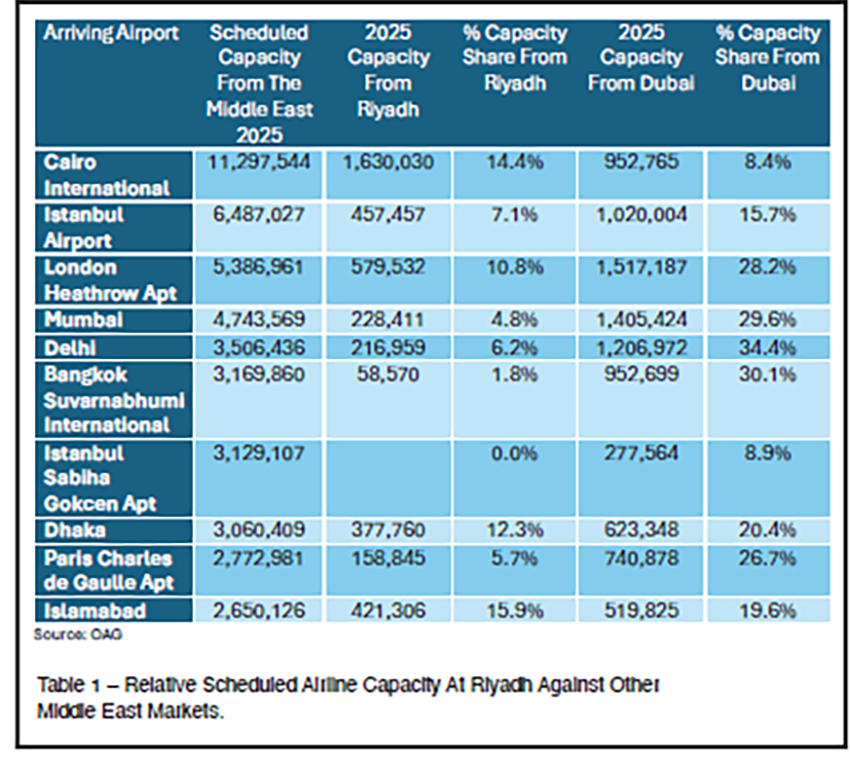

A review of current capacity from Riyadh to the ten largest non-regional markets from the Middle East (see table on left column of page 27) highlights the scale of challenge to be faced in the coming years.

Aside from Cairo, historically a very large local market, Riyadh’s respective share of capacity is very small compared to Dubai, the market leader in the region.

Intriguingly for the Saudi authorities, balancing the development of international services to destinations such as Dubai and Cairo from regional markets needs to be offset by allowing those overseas airlines access to valuable connecting traffic that would otherwise route through either Jeddah, or increasingly Riyadh.

Regional Saudi airports are longing for direct international connectivity, but that increases the competition across the two planned local hubs. Against such a backdrop it will be interesting to see how the desire for open skies plays versus protecting local airline interest.

With over 330 aircraft on order across the major airlines in Saudi Arabia there will be a flood of capacity that will increase competition and place pressure on air fares for all airlines, which might make for some painful results for more niche operators. And that’s before we add the India factor into the mix.

THE INDIA FACTOR

India has been a source of valuable connecting traffic through the Middle East, but as far as the Indian airlines are concerned, enough is enough and they want a slice of that market.

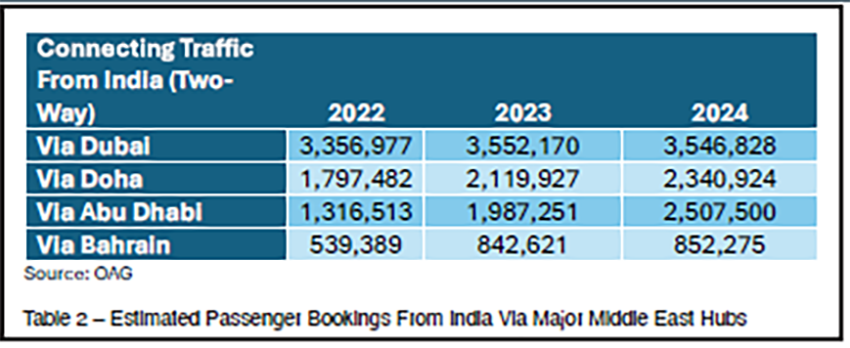

The table above (right) shows the recent scale of connecting traffic through some Middle East hubs. With India’s vibrant low-cost airline, Indigo, launching non-stop Europe services, competition will be increasing around the existing major hubs.

Interestingly, Emirates’ traffic volumes have been consistent over the last three years which may in part be a revenue management play linked to the amount of capacity the airline can operate to India.

In recent years the airline has sought more capacity, and regular approaches have been rejected by Indian authorities as they seek to rebalance how traffic flows through the Mumbai and Delhi hubs.

At the same time, growth of some 30% connecting traffic over Doha reflects from a 14% increase in capacity to India, and highlights Qatar Airways’ interest in developing more business from the market.

With new airports in Delhi and Mumbai, local airlines are already reshaping domestic networks to use existing slots for more international capacity.

In both cases taking sixth freedom, connecting traffic from the Middle East to Southeast Asia is a major part of development strategy and that means a more competitive market, especially for lower yielding worker segments.

Depending on your position, the Middle East will in the next decade either offer some of the greatest opportunities for new business and development or become one of the most fiercely competitive markets on the planet.